Kelsey Rogers

Principal

This article originally appeared in the June 2017 issue of Facility Executive. View the article on Facility Executive’s website here.

Dining spaces are the heart of many buildings, from single-family homes to large senior living communities. Mealtimes bring people together, providing an opportunity to bond with friends and family over the day’s events. Unfortunately, this isn’t always as easy as it sounds—we’ve all had the experience of going out to a restaurant and being unable to hear and follow the conversation of our dining partner, overwhelmed by the noise of conversations at tables nearby. As we raise our voices to be heard over the din, other dining patrons raise their voices, and the noise level escalates out of control. Poor acoustics in dining spaces leave us fatigued, rather than relaxed after enjoying a social outing.

This dining space at Kendal on Hudson retirement community in Sleepy Hollow, NY was designed by DiMella Shaffer Architects. (Photo: ©Robert Benson Photography)

In an ordinary dining facility, acoustical design to mitigate this buildup of activity noise is straightforward: include a significant area of sound absorptive treatment, minimize table size, and maximize the distance between adjacent tables. Selecting appropriate finish materials that absorb sound and blend with the architecture of the space, and determining an acoustically favorable seating layout that meets the functional and economic requirements of the facility, requires close collaboration with the design team; but the acoustical design strategy is typically simple and achievable.

For several reasons, dining spaces in senior living facilities are not “ordinary.” Residents often eat every meal, every day, in the same room. The acoustical design is inherently more important to these diners, who aren’t just visiting for an occasional meal. More importantly, and more often overlooked: many residents suffer from hearing impairment. So how does this translate to successful acoustical design? Even if there weren’t a practical limit as to how much sound absorptive treatment we could add, would that be the right thing to do?

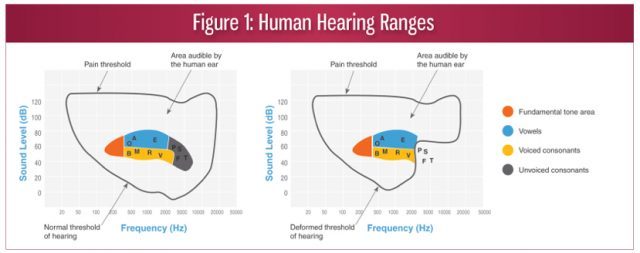

To answer this question, we need a more nuanced understanding of hearing loss. As we age, we lose hearing sensitivity in the mid- and high- frequency (pitch) range. This happens to be the frequency range that is critical for understanding consonants in speech.

Figure 1 (seen below) shows speech content in normal (left) and impaired (right) hearing ranges. The impaired hearing range graphic illustrates that with age, we lose the ability to hear “unvoiced consonants”: letters like “p”, “k”, “s”, and “t”. Without perception of consonants, it is very difficult, if not impossible, to understand words. For example, what is the difference between “pat”, “cat”, and “sat”? The difference is unvoiced consonants, without which we would only hear the vowel sound “a”.

Given the high instance of hearing loss in residents of senior living facilities, the acoustical design of large dining spaces requires a more innovative approach. In addition to including sound absorptive finish materials, minimizing table size, and maximizing distance between tables, the design has to provide acoustical support in the high-frequency range of unvoiced consonants.

This implies, counterintuitively, that carefully designed sound reflective surfaces are actually needed in the space—but their specific size, weight, shape, and angle are all critical to support high-frequency sounds appropriately. If the reflector is too heavy, it will reflect low frequency vowel sounds, which are already prevalent in the room. If the reflector is angled or placed incorrectly, it will send the sounds of conversation at one table to other tables nearby—exactly what we want to avoid. But at just the right height above a table, a small, lightweight reflector will support those “p” and “k” sounds so that residents can enjoy relaxing meals, and actually understand what their dining partners are saying.

Of course, the acoustical design of these reflectors has to be integrated with the architecture, lighting, and mechanical, electrical, and plumbing systems—no small task.

A successful design won’t just include architectural and acoustical modifications, but behavioral ones, too. Engaging the resident community and dining staff with the design team is crucial to developing a solution that suits everyone’s needs. For example, the seating configuration needs to be efficient for staff and residents to navigate, while minimizing the opportunity for people to congregate close to dining tables. Dining staff should also be trained in the most effective way to speak intelligibly to hearing-impaired residents—not just by speaking more loudly, but also by speaking more slowly, and with clear articulation. A successful senior living facility should provide multiple dining options to residents, varying in size and atmosphere (acoustical and otherwise).

Setting reasonable expectations for everyone is a key step in the design process, and it’s one with which an acoustics simulation and rendering technology can be used to help. Describing what a room will sound like is often confusing and unproductive. By building an acoustical computer model of the room and using a specially calibrated array of loudspeakers, we can actually listen to what the space will sound like before any costly renovations are made. Acentech’s 3D Listening® Studio is a tool that uses this technology.

For a space at the heart (and stomach) of a community, it’s important to cater both good food and good acoustics to everyone.