This article originally appeared in Xconomy Boston. View the article on Xconomy’s website here.

Architects are starting to embrace virtual reality as a tool for showing clients what their future buildings could look like. Now, Acentech wants to integrate audio simulations so they can hear what the spaces would sound like, too.

The Cambridge, MA-based consulting business spun out of the renowned BBN Technologies (now owned by Raytheon) more than 25 years ago, says Acentech president Jeffrey Zapfe. Acentech provides a mix of services to clients, but it’s best known for its expertise in room acoustics and noise control.

Acentech has started applying that knowledge to virtual reality. I recently visited Acentech’s headquarters and tried one of its VR demos: a recently constructed recital hall on the University of Massachusetts Boston campus. The 62-person company has experimented with combining audio simulations and images of spaces, heard and viewed through an Oculus Rift VR headset, to create a more immersive experience for clients.

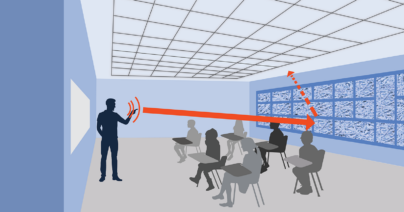

Before I sampled a jazz tune and other music in VR, Benjamin Markham, the director of the company’s architectural acoustics group, explained that Acentech began creating audio simulations of unbuilt structures and spaces more than a decade ago. Acentech employees record real-world sounds—people speaking, cars passing by on the highway, and so forth—and use software to render how those sounds might resonate in the future space, under various design scenarios.

Acentech uses the rendering to make recommendations that can limit noise (think thicker windows) or improve the acoustics (like installing fabric panels or other materials that absorb sound). Acentech has consulted on the design of concert halls, business offices, libraries, and swimming pools, among other spaces.

Typically, clients experience the sound simulations in a specially designed room in Acentech’s headquarters, equipped with a large screen to view project renderings and a set of speakers placed around the room for a more encompassing sound. Virtual reality was a natural next step.

“You really feel like you’re in the room,” Markham says. “That’s really exciting to kind of bridge the audio and video in a compelling way.”

The downside? Some of the “spatial realism” delivered by the speaker system gets lost when listening to the less immersive sounds coming from the VR device’s headphones, Markham says.

Outside of video game enthusiasts, VR devices have yet to generate a ton of interest among consumers. But Acentech is an example of how businesses are finding ways to utilize the technology.

Companies have already sprouted up to create VR experiences specifically for architecture and design, including IrisVR and VRtisan. Others are developing VR applications as a piece of their business. For example, Boston-based online home goods retailer Wayfair (NYSE: W) has released a VR app that helps shoppers design a backyard patio, as well as an augmented reality app that enables homeowners to visualize what a piece of furniture might look like in their living room.

Increasingly, architectural firms are “either toying with or fully invested in using VR as part of their process of working with their clients,” Markham says. Acentech sees its audio content as a useful component to plug into those experiences.

“It’s like being a post-production guy at a movie studio,” says Matthew Azevedo, Acentech staff scientist. “When people are shooting movies, they need sound effects and music. As our architecture clients go from people who make static pictures to people who make [interactive experiences], they’re going to want content for your ears to go with that.”

For my demo, I strapped on an Oculus Rift headset and was transported to the new UMass recital hall, where I experienced the acoustics from three different vantage points, including a seat near the stage, a center seat located further back, and a seat off to the side. The sounds of music—including a choir and a jazz band—filled my ears while I craned my head around to gawk at the empty 150-seat hall.

Notably, the demo isn’t designed to allow the person experiencing it to walk around and hear the sound from any location in the hall. That would require processing a lot more data, Azevedo says. Acentech could do it, Markham contends, but it would be time-consuming and more expensive. He expects the company will help produce “walkthrough VR simulations” in the future, “as acoustical modeling technology and computational horsepower both continue to improve.”

At the click of a button, Azevedo toggled between various orientations of the hall’s sound-absorbing curtains, to show how the space’s acoustics could be adjusted to match the musical style and type of performance group. You want more reverberation when a choir is singing a piece written for a vast cathedral, for example, but less reverberation with a jazz band, so that the fast-moving notes from the various instruments don’t get muddled.

“We build variability into the [acoustic] design so this could go from a big, reverberant, church-like space to a very dry, jazz-like space, and a whole bunch of stuff in between,” Azevedo says.

Acentech has created one other VR experience so far, Markham says, but he declined to share details.

With the UMass VR demo, Acentech created the visual rendering itself by taking photos of the completed hall using a spherical camera. But the plan for most of its future projects is for partner architectural firms or VR software companies to handle the visual part, Markham says. The projects might involve renderings of spaces that have yet to be built, or of proposed renovations to existing spaces, he says.

“While we are officially not the visual people, architects are,” says Azevedo, pictured above wearing the Oculus Rift headset. “They are all chomping at the bit to be using this technology in the design process.”

Articles

Articles