“To Honk or Not To Honk”: Some Thoughts on Car Horns

I grew up on the outskirts of a quiet and remote town, way up north. Like many teenagers, I was thrilled at the prospect of learning to drive as soon as I was old enough to get my learner’s permit. When my father would accompany me during those early days on the road, he advised caution, patience, and a steady hand behind the wheel. When he noticed my frustration with other drivers, he would often recite a maxim: “You never need to honk your horn in Fairbanks, Alaska.” To him, the sound of a car horn was a hostile sign of aggression, an unwelcome disturbance of the peace in our close-knit, small-town community.

After I got my driver’s license and hit the road without parental supervision, I was finally free to honk my horn as often as I liked. At the time, I saw this as a subversive expression of teenage rebellion. After all, the car horn is a versatile instrument well-suited for a variety of purposes – not just to register disapproval of other drivers’ behavior. A honk could be used to signal my arrival at a friend’s house, or as a “hello” to an acquaintance walking down the sidewalk. A honk aimed in solidarity at a group of protestors could be used to express my support for a political cause. A honk could even be used to get the attention of another motorist driving a car of the same make and model as mine, so that we might mutually admire each other’s taste in automobiles.

Eventually, after the novelty of my newfound freedom and youthful boisterousness began to fade, I started to see the importance of using my car horn in moderation. Indiscriminate honks can result in a variety of negative consequences – waking people who are trying to sleep, startling innocent passersby, and generally contributing to the din of cities and towns that are already afflicted by noise pollution.

To discourage haphazard horn honking, a number of organizations and governing bodies have issued guidance or laws to regulate it. The Vienna Convention on Road Traffic, which was developed in 1968 by the United Nations Economic and Social Council, states that: “Audible warning devices may be used only: (a) to give warning with a view to avoiding an accident; (b) outside built-up areas when it is desirable warn a driver that he is about to be overtaken.” This particular treaty was not ratified by the United States, but a number of states have passed their own statutes to regulate to horn use. In Massachusetts, “no person operating a motor vehicle shall sound a bell, horn, or other device…so as to make a harsh, objectionable, or unreasonable noise.” In California, a similar statute was recently challenged in court when a woman who was ticketed for honking while driving past a protest argued that it was a violation of her First Amendment right to political expression. The Court of Appeals was not convinced.

In acoustics theory, the term “horn” is typically used to describe a tube-shaped device with an increasing cross-sectional area. Sound waves originate at the small or “throat” end. As sound travels down the gradually flaring tube, the shape of the wavefronts remains consistent, and the acoustic impedance decreases to be more similar to that of open air. The energy that leaves the tube at the “mouth” end of the horn is radiated over a larger cross-sectional area, making the sound transmission more efficient. The earliest car horns utilized this principle with a simple mechanical sound source, such as in the image above. Squeezing the bulb pushes air through a reed in the throat of the horn, and the resulting sound waves are amplified as they radiate from the mouth.

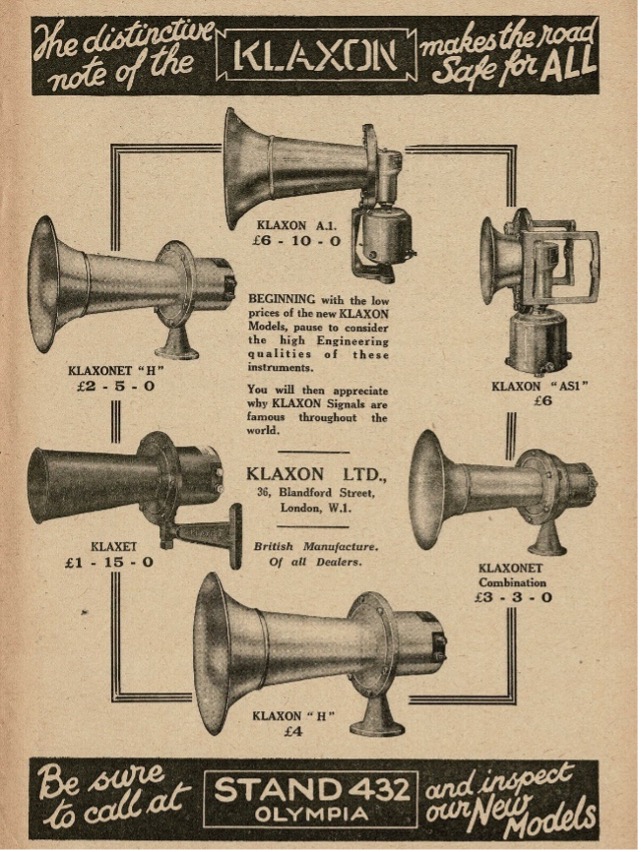

Another early car horn was the klaxon. Instead of a reed as the sound source as in the example above, a klaxon uses a steel diaphragm. When a cogwheel rotates against the diaphragm, it pushes the diaphragm in and out at the throat of the horn, producing the characteristic “aWOOga” sound we might associate with old-timey cartoons. The first klaxons were purely mechanical, being driven by a hand crank, but later versions were motor driven.

Most modern vehicle horns still use a vibrating diaphragm as the sound source, but they are driven electromagnetically, and the resulting honk is smoother than that of the klaxon. In fact, if the diaphragm is large enough, newer models no longer even need the classic flared structure to amplify the sound, technically making them “horns” in name only.

Many modern car horns have evolved to produce not just one tone but two, with a minor third being the most common interval. The rationale is that a horn emitting two tones simultaneously will stand out better than a single tone, which could more easily blend in with the ambient noise in a city or other noisy environment. Theoretically, it seems like a horn that stands out more would be preferable, but this speaks to the conundrum of car horns, truck back-up beeps, and other life safety alarms. On one hand, we want them to be loud and noticeable enough to alert people of imminent danger and give them the chance to steer clear. But the increased prevalence of people honking their horns superfluously – to express anger, frustration, excitement – results in roads that are more cacophonous and disorienting. This, in turn, leads to more anxious drivers who may feel the need to honk more often to assert themselves behind the wheel – essentially a vehicular variation of the Lombard effect.

Perhaps the responsibility lies with each of us to keep a cool head and a steady hand.